Readings:

Psalm

8

1

Chronicles 29:10-13

1

Corinthians 15:50-52

John 1:43-51

Preface of God the Father

[Common of an Artist, Writer, or Composer]

[For Artists and Writers]

PRAYER (traditional language)

O God of earth and altar, who didst give G. K. Chesterton a ready tongue

and pen, and inspired him to use them in thy service: Mercifully grant

that we may be inspired to witness cheerfully to the hope that is in us;

through Jesus Christ our Savior, who livest and reignest with thee and

the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

PRAYER (contemporary language)

O God of earth and altar, you gave G. K. Chesterton a ready tongue and

pen, and inspired him to use them in your service: Mercifully grant that

we may be inspired to witness cheerfully to the hope that is in us; through

Jesus Christ our Savior, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit,

one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

This commemoration appears in A Great Cloud of Witnesses.

Return to Lectionary Home Page

Webmaster: Charles Wohlers

Last updated: 14 April 2019

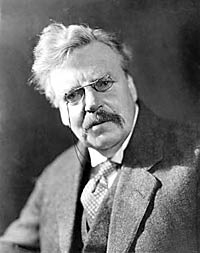

GILBERT KEITH CHESTERTON

APOLOGIST and WRITER, 1936

Gilbert

Keith Chesterton was born in London in 1874. He became a well-known writer

and lecturer. He was officially received into the Roman Catholic Church

in 1922, but had been writing from a Romanist point of view for a long

time before that. Some of his writing is specifically Roman Catholic,

and (in my judgement) he sometimes attacks Protestant positions without

troubling to understand them. However, much of his writing is "generic

Christian," and is read with profit and delight by many theologically

well-informed Protestant readers. If you are a Protestant, you will have

to read him with your mind in gear, but then you have no business to read

anything whatsoever with your mind out of gear.

Gilbert

Keith Chesterton was born in London in 1874. He became a well-known writer

and lecturer. He was officially received into the Roman Catholic Church

in 1922, but had been writing from a Romanist point of view for a long

time before that. Some of his writing is specifically Roman Catholic,

and (in my judgement) he sometimes attacks Protestant positions without

troubling to understand them. However, much of his writing is "generic

Christian," and is read with profit and delight by many theologically

well-informed Protestant readers. If you are a Protestant, you will have

to read him with your mind in gear, but then you have no business to read

anything whatsoever with your mind out of gear.

Chesterton died 14 June 1936, but is here commemorated two days earlier because the later days are taken.

One of his concerns was literary criticism. He wrote books on Robert Browning and Charles Dickens, with prefaces to the individual Dickens novels. He also wrote books and monographs on George Bernard Shaw, William Blake, William Cobbett, Robert Louis Stevenson, and The Victorian Age in Literature.

He also wrote fiction, his best known work being a series of detective short stories featuring a priest, Father Brown, who (somewhat after the matter of the TV sleuth Columbo) tends to give the appearance of being a harmless, bumbling, absent-minded fellow, but who always notices the detail that enables him to solve the case. Often, he connects the reasoning that solves the case with the sort of reasoning that is involved in Christian life. (I suspect that Harry Kemelman, author of Friday the Rabbi Slept Late, Saturday The Rabbi Went Hungry, and other works, may have gotten the idea for his detective, Rabbi Small, from Father Brown.) There is a film, The Detective, starring Alec Guinness, based on the Father Brown stories.

Less known, but a particular favorite of mine, is his novel, The Man Who Was Thursday. It is an adventure story, an action yarn, about a man who finds himself involved with, and accepted as a member of, a gang of anarchists. (For the purposes of the story, one accepts the notion of anarchists as simply motiveless terrorists, engaged in destruction for its own sake, not to be confused with men like Albert Jay Nock or Henry David Thoreau, who were anarchists in a very different sense.)

The tone of the story (as of every Chesterton story) is strongly affected by the exuberant style of the author. There is a scene in a restaurant, where the protagonist has the task of delaying another man for a few hours, and decides to pick a quarrel with him in order to do so. A musician is playing something by Wagner in the background. He approaches the other man's table and is about to attack him. The man's companions hold him back, but he cries out,

"This man has insulted my mother!"

"Insulted your mother? What are you talking about?"

"Well, any way, my aunt."

"How could he have insulted your aunt. We have just

been sitting here talking."

"Ah, it was what he said just now."

"All I said was that I liked Wagner played well."

"Aha! My aunt played Wagner badly. It is a very tender

point with our family. We are always being insulted over it."

And so the story continues, a thriller with comic pauses, But as one reads, one begins to realize that the writer actually has something deeper in mind, a commentary on the Book of Job.

Chesterton had strong political interests. During the war between Britain and the Boer Republic of South Africa, he was strongly and openly pro-Boer, regarding the war as a straightforward attack by a large country on a small one. During World War I, he regarded England as the underdog, and rallied to her cause with enthusiasm. His long-term political and economic position was something called Distributivism, of which some of his admirers complained that it was not a political program, but simply at attractive picture. As far as I understand it, it involved the redistribution of land, so that everyone would have his own cottage and his own plot of land, and would grow his own food and be self-sufficient. As the prophet says (Micah 4:4),

Every man shall sit under his own vine and under his own fig tree, and none shall make them afraid.

He is, as far as I have read, quite vague on how he proposes to bring this about, or how a society of peasant proprietors will manufacture industrial machinery, or how a country that has forsworn industrial development will resist invasion from a country that has not.

Still, it is an appealing idea. When I was teaching courses for the Washington Area Free University back in 1969-70, courses in Natural Theology, Free-Market Economics, Fortran Programming, and Bread-Baking, it was the bread course that had the waiting list. And the late Karl Hess, who encouraged inner-city dwellers to do such things as grow food fish in ponds on the roofs of their apartment buildings, and vegetables in window boxes, found that nothing he talked about aroused greater interest. He tried the experiment of throwing one sentence on producing goods for one's own family into the middle of a lecture on something else. During the question period, the audience would always zero in on that topic. Very possibly that is where a Distributivist would begin--by saying, for example, to a married couple both of whom had outside jobs:

You say that you need both incomes to keep afloat. But, because Kathy is working eight hours a day as a sales clerk, she hasn't time to prepare meals from scratch, so all the waffles are pop-tarts, all the cakes come from the bakery, all the chicken comes from the store already fried, and it all costs so much that you need two incomes to pay for it. Actually, Kathy, if you stayed home and baked cakes and fixed meals from scratch, and cared for a garden, you and your family would eat better and save more money than you are currently bringing in, and you might find that gardening and cooking and home-schooling the youngsters (who would help in the kitchen and learn fractions while following recipes) was more satisfying and less boring than eight hours a day selling cosmetics. Of course, if your job is something more exciting, like being an astronaut, you might object to giving it up to grow strawberries and to bake cookies and to teach your children to swim and to fry an egg, and to explain to them how yeast makes bread rise and baking powder makes muffins rise, and so on. But most jobs, for men or women, are not very exciting, and you might want to consider your options.

Come to think of it, I can easily imagine Chesterton saying just that. In the early days of this century, he said, "A liberated woman is one who rises up and says to her menfolk, 'I will not be dictated to,' and proceeds to become a stenographer."

One thing that will jar on the ear of most readers of Chesterton in the closing years of the 20th century is his casual mention of racial and ethnic stereotypes. Before the rise of Naziism, this was a common habit among many persons of good will. Some critics have called Chesterton anti-Jewish. It would be more accurate to call him anti-banking, or anti-capitalist. David Friedman (son of Milton Friedman), who is Jewish, pro-capitalist, and an enthusiastic admirer of Chesterton, devotes a chapter to his defense in his book, The Machinery of Freedom.

Chesterton (widely known as GKC) was an essayist who wrote a regular newspaper column for much of his life. Many of his books are collections of his essays and columns, covering a wide range of subjects, so that the collection titles are like: All Things Considered, All Is Grist, Generally Speaking, and so on. One famous series for which he did not get paid was an exchange with Robert Blatchford, editor of The Clarion, in 1903-4. Blatchford was an atheist, a Socialist, and a determinist, convinced that Science had shown that every physical event is part of a causal chain going back indefinitely, so that there can be no such thing as free choice. If Adam ate of the forbidden fruit, it must be that his psychological makeup rendered this inevitable. He wrote:

Now, then, did God make Adam? He did. Did God make the faculties of his brain? He did. Did God make his curiosity strong and his obedience weak? He did. Then, if this man Adam was so made that his desire would overcome his obedience, was it not a foregone conclusion that he would eat that apple? It was. In that case, what becomes of the freedom of the will?

To this, GKC replied that, according to Blatchford, men act as prior causes determine that they must act, and therefore Christians are mistaken in blaming them for their actions. But Christians, as GKC hastens to point out, are not the only ones who blame men for their actions.

The Christian fantasy crops up in the most unlikely places. Even In the Clarion, for instance, I have seen writers distributing a grave and tender blame... to those who adulterate milk and butter and rack-rent slums. But you, on your principle, hold all these men guiltless.... You have discovered something infinitely more sensational and modern than any dusty Bible criticism: you have discovered this lucid and interesting fact --that whether Lord Penrhyn starves himself to save his men or saves himself by putting poison in their beer, he is equally spotless as the flowers of spring.

Blatchford replied that, though we do not blame a man who burns a house down, any more that we blame a shark who devours a baby, we can still take steps to resist him. Just so, the editor of the Clarion can give a careless clerk a scolding, as part of the educational process. GKC seized on this example with delight, and replied:

On your principles, you would say: "My blameless Ruggles, the Anger of God against you has once more driven you, a helpless victim, to put your boots on my desk and upset the ink on the ledger. Let us weep together." If that is the way clerks are scolded in the Clarion office, gaily will I now apply for the next vacancy in that philosophical establishment.

His poems vary widely. Some are pure nonsense rhymes, written strictly for the fun of it. Others are fun, but with a point behind it. For example, a Spiritualist paper, remarking on the conversion of a former Roman Catholic to Spiritualism (meaning what we now call "channeling," or communicating with the spirits of the dead through a "medium" or "channel," a psychical sensitive go-between), said, "When men like Mr Dennis Bradley can no longer be content with the old faith, a spirit of jealousy is naturally aroused." (Who is Dennis Bradley, and what are his claims to eminence? I have no idea.) GKC replied to this with a six-stanza poem, Jealousy, of which I reproduce the first two.

She sat upon her Seven Hills;

She wrapped her scarlet robes about her,

Nor yet in her two thousand years

Had ever grieved that men should doubt her.

But what new horror shakes the mind,

Making her moan and mutter madly?

Lo, Rome's high heart is broke at last:

Her foes have borrowed Dennis Bradley.

If she must lean on lesser props

Of earthly fame or ancient art,

Make shift with Raphael or Racine,

Put up with Dante or Descartes,

Not wholly can she mask her grief,

But touch the wound and murmur sadly,

"These lesser things are theirs to love

Who lose the love of Mr. Bradley."

Not all his poems are intended to make the reader laugh. His longest poem (about 2800 lines) is called The Ballad of the White Horse, and deals with King Alfred the Great (26 Oct), who in 878, having been backed into a corner by the heathen Danish invaders, won a decisive battle and saved England from total destruction. The poem deals with the military situation, but also with contending philosophies. Alfred, unrecognized, is brought into the Danish camp as a wandering harpist, and he and four Danes, including the king, play songs expressing their views of life. My view is that the poem is well worth reading, but could be improved by a little abridgement (for example, I would cut everything in the Preface after the line, "and laid peace on the sea").

A shorter poem, Lepanto (about 150 lines) deals with the sea-battle of Lepanto, fought in 1571 near the entrance to the Gulf of Corinth (separating Northern from Southern Greece) between the Turks and a Christian alliance (mostly Spain, Venice, Malta, the Papal States, and other Italian states), led by the King of Spain's half-brother, Don John of Austria. The Turks lost nearly all their ships, and nearly 10,000 of their galley slaves, mostly Christians, were freed. Cervantes, author of Don Quixote, fought with great distinction, being wounded three times and losing the use of his left hand. A snippet:

In that enormous silence, tiny and unafraid,

Comes slowly up a winding road the noise of the Crusade.

Strong gongs groaning as the guns boom far,

Don John of Austria is going to the war.

Stiff flags straining in the night-blasts cold,

In the gloom black-purple, in the glint old-gold,

Torch-light crimson on the copper kettle-drums,

Then the tuckets, then the trumpets, then the cannon and he comes.

Don John laughing in the brave beard curled,

Spurning of his stirrups like the thrones of all the world,

Holding his head up for a flag of all the free.

Love-light of Spain--hurrah!

Death-light of Africa!

Don John of Austria

Is riding to the sea.

In both poems, Chesterton points out near the end that the victory does not mean that the struggle is over. The Danes did not quietly disappear, nor did the Turks. Neither do successfully resisted temptations and sins in the life of the Christian. We must not expect, this side of Heaven, to reach a point where all our problems are solved and all struggles are over. (John 16:29-33)

Two biographies by GKC are St. Francis of Assisi and St. Thomas Aquinas. Neither of them is crammed with dates and factual details, but both have been highly praised for their insights into the character of the men described. Etienne Gilson, the foremost Aquinas scholar of the twentieth century, calls GKC's book "the best book ever written on St. Thomas." If his book on Francis is not as good, it is perhaps because Francis is far harder to write about. What one needs to express is the spirit of Francis, his personality, the spiritual air he breathed. And this is a tall order.

Chesterton also wrote a book called Heretics, in which he offers a critique of some of the prominent philosophies and philosophers of his time (1905)--men like Frederick Nietzsche, H G Wells, G Bernard Shaw (these last two both good friends of his). He says of Shaw (approximately):

He tells us that our lives must be based on Will. He says to Us, "Will something," which is to say, "I do not care what you will," which is to say, "I have no will in this matter." In this, he is the mirror image of the Buddhist, who tells us to cultivate Holy Indifference. The Buddhist and the Shavian stand at the cross-roads, and one of them hates all the roads, and one of them loves all the roads. The result--well, some things are not difficult to predict. They stand at the cross-roads.

He followed this three years later by Orthodoxy, an account of his own beliefs, with an indication of the considerations that had led him to them.

Chesterton's principal work of apologetics, of straightforward, direct defence of Christian belief, is The Everlasting Man (1925). It is divided into two parts, "The Animal Called Man" and "The Man Called Christ." Chesterton undertakes to refute, first, the view that man is just one more species of animal, not different in principle from the other species, and second, the view that Christ is just one more religious or moral teacher, and Christianity just one more religion, not different in principle from the others. It may be noted that here Chesterton is defending the Christian faith, as held by all who acknowledge Jesus Christ as Lord, God, and Savior.

— by James Kiefer

A number of the above books and more are available from the Internet Archive. Links to just about everything about Chesterton on the Web may be found at: http://www.cse.dmu.ac.uk/~mward/gkc/index.html