Readings:

Isaiah 32:11-18

Psalm 35:23-28

Hebrews 2:10-13

Luke 4:14-21Preface of Saint (2)

[Common of a Prophetic Witness]

[Common of a Saint]

[For Prophetic Witness in Society]

[For Reconciliation and Forgiveness]

PRAYER (traditional language)

Almighty God, we bless thy Name for the witness of Frederick Douglass, whose impassioned and reasonable speech moved the hearts of people to a deeper obedience to Christ: Strengthen us also to speak on behalf of those in captivity and tribulation, continuing in the way of Jesus Christ our Liberator; who with thee and the Holy Spirit dwelleth in glory everlasting. Amen.

PRAYER (contemporary language)

Almighty God, we bless your Name for the witness of Frederick Douglass, whose impassioned and reasonable speech moved the hearts of people to a deeper obedience to Christ: Strengthen us also to speak on behalf of those in captivity and tribulation, continuing in the way of Jesus Christ our Liberator; who with you and the Holy Spirit dwells in glory everlasting. Amen.

Lessons revised at General Convention 2024.

Return to Lectionary Home Page

Webmaster: Charles Wohlers

Last updated: 22 Dec. 2024

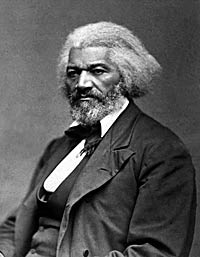

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

SOCIAL REFORMER, 1895

Frederick

Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, circa 1818 –

February 20, 1895) was an American abolitionist, women's suffragist, editor,

orator, author, statesman and reformer. Called "The Sage of Anacostia"

and "The Lion of Anacostia", Douglass is one of the most prominent

figures in African American and United States history.

Frederick

Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, circa 1818 –

February 20, 1895) was an American abolitionist, women's suffragist, editor,

orator, author, statesman and reformer. Called "The Sage of Anacostia"

and "The Lion of Anacostia", Douglass is one of the most prominent

figures in African American and United States history.

He was a firm believer in the equality of all people, whether black, female, Native American, or recent immigrant. He was fond of saying, "I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong."

Frederick Douglass was born a slave in Talbot County, Maryland. He was separated from his mother, Harriet Bailey, when he was still an infant. She died when Douglass was about seven and Douglass lived with his maternal grandmother Betty Bailey.

When Douglass was about twelve, his owner's wife started teaching him the alphabet, which was against the law. Douglass succeeded in learning to read from white children in the neighborhood and by observing the writings of men with whom he worked. As Douglass learned and began to read newspapers, political materials, and books of every description, he was exposed to a new realm of thought that led him to question and then condemn the institution of slavery.

He was hired out to a number of owners before finally escaping north to freedom in September 1838. Douglass continued traveling up to Massachusetts. There he joined various organizations in New Bedford, including a black church, and regularly attended abolitionist meetings.

Douglass' best-known work is his first autobiography Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, published in 1845. The book received generally positive reviews and it became an immediate bestseller. Douglass published three versions of his autobiography during his lifetime (and revised the third of these), each time expanding on the previous one. The 1845 Narrative, which was his biggest seller, was followed by My Bondage and My Freedom in 1855. In 1881, after the Civil War, Douglass published Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, which he revised in 1892.

Douglass produced some regular abolitionist newspapers, including The North Star. Its motto was "Right is of no Sex — Truth is of no Color — God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren."

Douglass believed that education was key for African Americans to improve their lives. For this reason, he was an early advocate for desegregation of schools.

Douglass conferred with President Abraham Lincoln in 1863 on the treatment of black soldiers, and with President Andrew Johnson on the subject of black suffrage. His early collaborators were the white abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips.

In 1848, Douglass attended the first women's rights convention, the Seneca Falls Convention, as the only African American. Elizabeth Cady Stanton asked the assembly to pass a resolution asking for women's suffrage. Many of those present opposed the idea, but Douglass stood and spoke eloquently in favor; he said that he could not accept the right to vote himself as a black man if woman could not also claim that right. His powerful words rang true with enough attendees that the resolution passed.

By the time of the Civil War, Douglass was one of the most famous black men in the country, known for his orations on the condition of the black race and on other issues such as women's rights. His eloquence gathered crowds at every location. His reception by leaders in England and Ireland added to his stature.

After the Civil War, Douglass was appointed to several important political positions. He served as President of the Reconstruction-era Freedman's Savings Bank; as marshal of the District of Columbia; as minister-resident and consul-general to the Republic of Haiti (1889–1891); and as chargé d'affaires for the Dominican Republic.

Douglass was an ordained minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

— more from Wikipedia